Teeth are hard, calcified structures in the mouth that help break down food into smaller pieces, making digestion easier. They work together to tear, cut, and grind food efficiently.

Each tooth is made of enamel, dentin, and pulp. Enamel is the hard, protective outer layer, dentin forms the main body of the tooth, and pulp contains nerves and blood vessels.

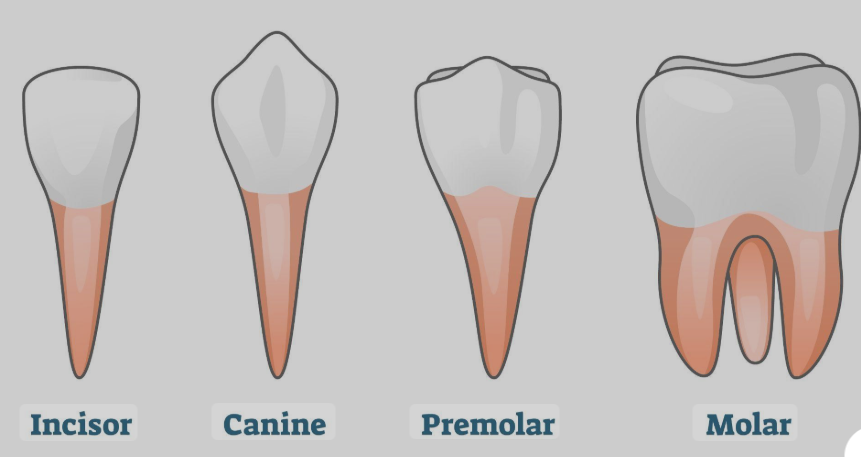

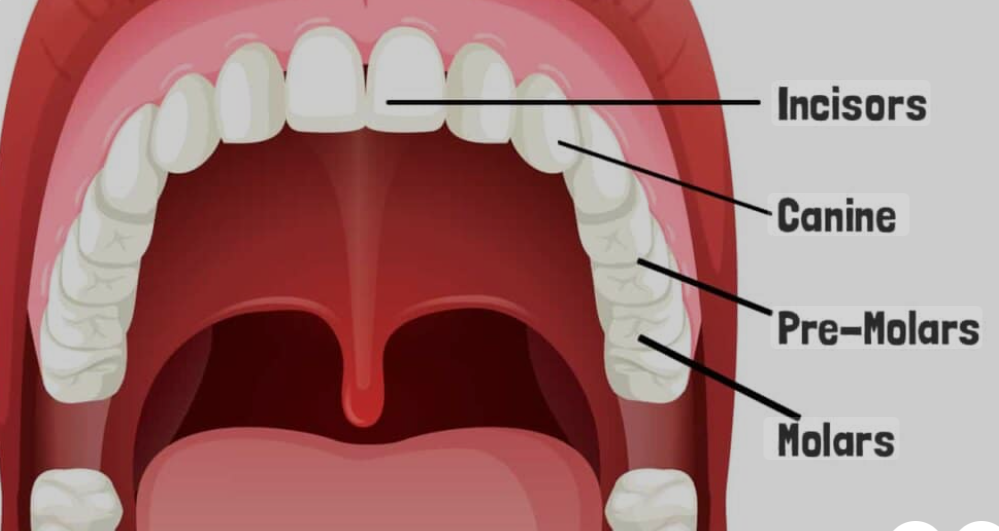

Teeth are classified by their shape and function. Some are sharp and pointed for cutting, while others are flat and broad for grinding. Each type plays a specific role in processing food.

Humans typically develop two sets of teeth in a lifetime: primary (baby) teeth and permanent (adult) teeth. The transition ensures proper jaw development and accommodates growing facial structures.

Teeth are anchored in the jawbone by roots, which provide stability and support. The surrounding gums and ligaments help absorb the forces from biting and chewing.

Beyond their functional role in eating, teeth contribute to the overall shape and appearance of the face. They support the cheeks and lips, helping maintain facial structure and expressions.

Types of Teeth

Central Incisors

Central incisors are the most prominent front teeth, located directly in the middle of both the upper and lower jaws, with two on the top and two on the bottom. They are the first permanent teeth to erupt, typically around ages 6-8, and feature a broad, flat surface with a sharp, chisel-like edge ideal for cutting and biting into food like fruits or vegetables. These teeth play a crucial role in speech articulation and provide aesthetic appeal by framing the smile.

Beyond their primary chewing function, central incisors support the lips and facial structure, helping maintain proper lip closure and preventing a “gummy” appearance. They are highly visible, making them prone to cosmetic concerns like discoloration, and require gentle brushing to avoid chipping due to their thin enamel layer. Regular dental check-ups ensure their alignment contributes to overall bite harmony.

Lateral Incisors

Lateral incisors sit immediately beside the central incisors on each side of both jaws, totaling four in the adult mouth. They erupt slightly later, around ages 7-9, and are slightly smaller and narrower than central incisors, with a similar chisel-shaped edge designed for slicing food and aiding in initial breakdown during chewing. These teeth enhance the symmetry of the front smile and assist in guiding food onto the molars for further processing.

In addition to their role in mastication, lateral incisors contribute to phonetic sounds like “f” and “v” and help stabilize the position of adjacent teeth. They are more susceptible to spacing issues or peg-shaped variations, which can affect aesthetics, so orthodontic evaluation may be needed if misalignment occurs. Proper flossing around them prevents plaque buildup in the tight spaces between front teeth.

Canines

Canines, also known as cuspids, are the pointed, fang-like teeth positioned next to the lateral incisors on each side of both jaws, with four total. They erupt around ages 9-12 and are the longest teeth in the mouth, featuring a single sharp cusp for tearing tough foods like meat and stabilizing the bite by interlocking with opposing teeth during jaw closure. Their robust roots anchor them firmly, supporting the overall dental arch.

These teeth serve as “cornerstones” for alignment, guiding the positioning of other teeth and preventing shifting over time. Canines also aid in facial muscle function and aesthetics by filling out the corners of the mouth. Due to their prominence, they are less prone to decay but can wear down from grinding; night guards may be recommended for protection in cases of bruxism.

First Premolars

First premolars, or first bicuspids, are located just behind the canines on each side of both upper and lower jaws, totaling eight. They typically erupt between ages 10-11 and have two cusps (points) on their biting surface, making them transitional teeth that combine cutting and crushing actions to further break down food particles before they reach the molars. Their broader crowns and two roots (especially in uppers) provide stability for side-to-side chewing movements.

These premolars assist in distributing occlusal forces evenly across the jaw, reducing strain on front teeth during meals. They are common sites for fillings due to their grooves that trap food, so sealants are often applied preventively. Maintaining their health supports efficient digestion by ensuring food is adequately prepared for swallowing.

Second Premolars

Second premolars follow the first premolars on each side of both jaws, with eight in total, erupting around ages 10-12. Slightly smaller than their predecessors, they feature two cusps and a flatter surface optimized for grinding and crushing softer foods, bridging the gap between tearing and full mastication. Their single root in lowers and bifurcated roots in uppers enhance grip and leverage during chewing.

These teeth contribute to the posterior bite balance, helping align the jaw for proper occlusion and preventing uneven wear on molars. They are less visible but vital for overall oral function, often requiring monitoring for cracks from hard foods. Fluoride treatments strengthen their enamel, promoting longevity and reducing sensitivity risks.

First Molars

First molars, often called “6-year molars,” are the large, flat teeth erupting behind the second premolars on each side of both jaws, with four total, around ages 6-7. They have four to five cusps and deep fissures for grinding and pulverizing food into a paste-like consistency, marking the start of serious chewing capacity in children. These are the first permanent posterior teeth, setting the foundation for the adult dentition.

Positioned toward the back, first molars support facial height and jaw development while enduring the heaviest chewing loads. Their complex surfaces make them decay hotspots, so early sealants are crucial. Healthy first molars ensure efficient nutrient absorption by thoroughly processing fibrous foods.

Second Molars

Second molars emerge behind the first molars on each side of both upper and lower jaws, totaling four, typically around ages 11-13. Larger than first molars with multiple cusps and broader surfaces, they excel at final-stage grinding of food, handling tougher items like nuts or grains to aid digestion. Their deep roots provide anchorage, but late eruption can sometimes lead to impaction if space is limited.

These molars finalize the posterior chewing system, promoting even wear across the dental arch and supporting speech by stabilizing jaw position. They are harder to reach for cleaning, increasing cavity risk, so interdental brushes are recommended. Preserving second molars maintains long-term bite integrity and prevents shifting of anterior teeth.

Baby Teeth

Baby teeth form the first set of 20 teeth in a child’s mouth, consisting of 10 in the upper jaw and 10 in the lower, with no premolars—instead featuring incisors, canines, and molars. They begin erupting around 6 months of age, starting with the central incisors, and are fully in place by age 3, featuring smaller crowns and shorter roots compared to permanent teeth to accommodate a developing jaw.

These teeth serve as placeholders to guide the eruption of permanent teeth, support early chewing of soft foods, and aid in speech development by shaping sounds like “s” and “th.” They also contribute to facial growth and jaw alignment; poor care can lead to misalignment later. Gentle brushing with fluoride toothpaste and avoiding sugary foods promote their health until natural shedding begins around age 6.

Wisdom Teeth

Wisdom teeth, or third molars, are the final set of four molars (two upper and two lower) that typically erupt between ages 17 and 25, often referred to as “wisdom” due to their late arrival in adulthood. They are the largest molars with multiple cusps for grinding tough foods, but their position at the very back of the jaw means they frequently lack space, leading to impaction or partial eruption.

These teeth can enhance chewing efficiency if they fit properly, but complications like crowding, infection, or decay often necessitate removal, especially if they cause pain or shift other teeth. Monitoring via X-rays during routine check-ups is essential, and extraction is common prophylactically in young adults to prevent future issues. Post-removal care includes soft diets and pain management for quick recovery.